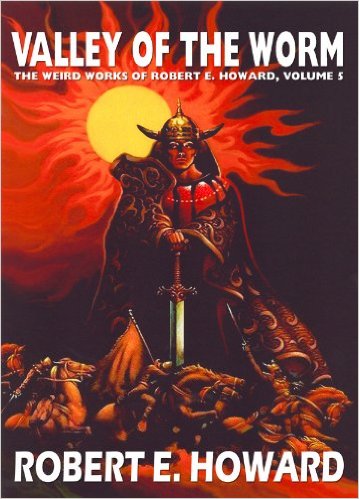

The Valley of the Worm

The Weird Works of Robert E. Howard, Volume 5

Edited by

Paul Herman

These ongoing pieces are overviews rather than reviews and therefore contain spoilers galore

All right, it’s admittedly unlikely in the extreme that he planned it this way; but if he had done so, then Weird Tales editor Farnsworth Wright could not have done a better job with the order in which he ran the initial four stories featuring Robert E. Howard’s last major hero – Conan of Cimmeria.

At this point it was obvious that the author was not going to be presenting his tales of the Hyborian Age warrior in any particular kind of chronological order. In fact he was later to say that he just wrote them down as if the adventurer himself were standing at his shoulder, reeling off random incidents from a wandering life. Yet by accident, rather than design, these initial four tales presented a remarkably cohesive introduction to the character.

In The Phoenix on the Sword and The Scarlet Citadel we were introduced to Conan in later life — as the King of Aquilonia, mightiest Western nation of the Hyborian lands.

In The Tower of the Elephant we went back several decades to Conan as a young thief in Zamora, newly arrived to civilization.

In Black Colossus (Weird Tales, June of 1933), which opens this fifth collection, we see him at some intermediate stage. He is a seasoned mercenary warrior, ready for his first real command, yet still with a lot to learn about the civilized nations.

Under Queen Yasmela of the Shemitish splinter state of Khoraja, which is now threatened by the reincarnated sorcerer Thugra Khotan, he is at least started on the road to eventual kingship, made explicit in this brief but powerful scene:

“’By Mitra’, said [Amalric] slowly, ‘I never expected to see you cased in coat-armor, but you do not put it to shame. By my finger-bones, Conan, I have seen kings who wore their harness less regally than you!’

“Conan was silent. A vague shadow crossed his mind like a prophecy. In years to come he was to remember Amalric’s words, when the dream became the reality.”

Just as Citadel is a mini-epic that followed on from the relatively intimate Phoenix, so too does Colossus follow a pattern when taken after the more pared-down scale of The Tower of the Elephant. It is full of intrigue and colour, as well as containing one of Howard’s enormously exciting sequences which feature the clashing together of armies in their tens of thousands. And in addition he manages to outline a considerable amount of detail concerning the geography of the Hyborian Age.

It’s not quite up to the standard of the previous three, but it is still the latest in a line of consistently good stories that Howard was now turning out with extraordinary regularity.

Also worth noting is the fact that this was his thirtieth piece over an eight year period for Weird Tales. Go back and compare Black Colossus with his debut in Spear and Fang at some stage. The realism and vividness of the storytelling has immeasurably improved, naturally; yet with that early piece some of the Howardian themes are already there in embryo form.

Having set up a substantial background for his hero, the July, 1933 issue of Weird Tales saw Howard (or more likely editor Wright) take a break from the Cimmerian with a short oddity set in the Texas of the writer’s day.

The Man on the Ground may be just a few pages long and feature only two characters, but it is as direct a statement as REH ever made on his themes of hate, revenge and the sheer bull-headedness of holding onto a grudge long after you’ve forgotten its origins. (A trait, I should probably be ashamed to admit, that I know of all too well.) Packed with little details and incidentals, this could only have been written by a young man who – as they would say these days – had some serious anger issues.

Hyborian Age S & M

When Weird Tales printed the next Conan outing in September of 1933, I could have wished for Farnsworth Wright to have kept Howard’s original title, Xuthal of the Dawn. To me that is apt to the theme of the story and so enticingly suggestive that I can almost see the lost city of Xuthal shimmering in the morning desert heat.

Yet perhaps the rather generic title that he renamed it with – The Slithering Shadow – is equally appropriate, since this nuts-kicking, blood–and-guts, headlong adventure is chock full of the images that later depictions of Conan draw heavily on.

We have the time-lost and decadent civilization, with its buried desert setting; there is the blunt straightforwardness and rough humour that made the character of Conan so much more than the usual sword-and-sandals cardboard cut-out; we even get a ‘beautiful hellcat-whips-beautiful innocent’ scene in a shamelessly gratuitous attempt to appeal to the then-popular ‘spicy tales’ market with a bit of early girl-on-girl S&M.

And of course it opens with a classic image that has been reproduced on paperbacks featuring dozens of various barbarian warriors in the decades since.

How familiar is this? And how many brilliant pieces of Frank Frazetta or Boris Vallejo artwork does it call to mind?

“The desert shimmered in the heat waves. Conan the Cimmerian stared out over the aching desolation and involuntarily drew the back of his powerful hand over his blackened lips. He stood like a bronze image in the sand, apparently impervious to the murderous sun, though his only garment was a silk loincloth, girdled by a wide gold-buckled belt from which hung a saber and a broad-bladed poniard. On his clean-cut limbs were evidences of scarcely healed wounds.

“At his feet rested a girl, one white arm clasping his knee, against which her blond head drooped. Her white skin contrasted with his hard bronzed limbs; her short silken tunic, low-necked and sleeveless, girdled at the waist, emphasized rather than concealed her lithe figure.”

From the seemingly endless sweeps of the southland desert to the seemingly endless sweeps of the Western Sea, Howard took one of his now-customary jumps in time for Weird Tales’ October issue and The Pool of the Black One.

Apparently, Conan has been guilty of a deed so bloody that he has had to flee his erstwhile companions of the Barachan pirates; and that gains him mighty respect amongst his new companions, the raiders of Zingara. Which gives REH an opportunity (and he was seldom one to miss such a thing) to comment on the innate hypocrisy of men:

“There was little favour in the gaze [Zaporavo] bent on Conan. Little love was lost between the Zingaran renegades and the outlaws who infested the Baracha Islands off the southern coast of Zingara. These men were mostly sailors from Argos, with a sprinkling of other nationalities. They raided the shipping, and harried the Zingaran coast towns, just as the Zingaran buccaneers did, but these dignified their professions by calling themselves Freebooters, while they dubbed the Barachans pirates. They were neither the first nor the last to gild the name of thief.”

Most Conan enthusiasts find The Pool of the Black One to be an entertaining if pedestrian enough work. And there’s a lot of truth in that. I find much to enjoy here; and there is a depiction of Conan’s character that we can also use in order to roughly place at what age he is likely to be. For instance, he is certainly at that stage where his alpha-male nature dictates that he must take command of any group he finds himself thrown into. He is also extremely ruthless in getting what he wants – and as Zaporavo finds to his cost, not a man to be dismissed lightly:

“He hesitated, and doing so, lost his ship, his command, his girl, and his life.”

I tend to be of the same opinion as those who believe that an ‘s’ has gone missing from the last word of this title. Certainly, it would make more sense of it if that’s true. But here’s an idea that I want to throw out there.

Of course, it may have occurred to others but I’ve never read anything on it: that final scene where the green waters of the abhorrent pool erupt and pour themselves after the fleeing buccaneers, driving forward, tentacle-like and even cutting a swathe into the ocean after the ship… I can’t help wondering if it wasn’t Howard’s tip of the hat to a classic story from his friend, H. P. Lovecraft. It was a story that he hugely admired and which had been published in these pages some years previously: The Call of Cthulhu.

Lost Knobs and Giant Worms

Old Garfield’s Heart (December, 1933) is one of the contemporary tales that Howard was writing more and more of around this time. It’s of a sequence that draws on Texas lore he would have heard when growing up and is set in the perhaps unfortunately named town of Lost Knob, which correlates to his own hometown of Cross Plains. It‘s a nice little piece.

In January Rogues in the House kicked off Conan’s 1934 WT appearances, with a tale of the Cimmerian as a young thief; and although this is set probably a couple of years after his apprenticeship in Zamora’s City of Thieves and which sees him as more accomplished and organised, there are still moments when he comes across as damned near feral.

I like this one for the smattering of Hyborian Age political ideas that REH throws in, as well as the fact that for a change there are no strictly supernatural elements. Although his epic battle with an evolved ape of the Vilayet region does elicit this interesting and surprisingly moving short monologue from Conan:

“I have slain a man tonight, not a beast. I will count him among the chiefs whose souls I’ve sent into the dark, and my women will sing of him.”

One of the most inexplicable rejections that Howard was ever to receive was for his manuscript, Marchers of Valhalla. Here he introduced the amputee, James Allison, who is simply living out his embittered existence in 1930s Texas until he learns how to awaken memories of previous lives as various mighty, brawling Aryan warriors of far-distant ages.

I have no idea why this first masterwork in the Allison saga came to be rejected since it contains a fascinating trawl through a pseudo-history that seems to be a portion of the Hyborian Age; blistering prose combined with headlong action; and a fascinatingly over-the-top barbarian hero. Found long after Howard’s death and at a time when it was thought that all the major works had appeared, it wasn’t to see publication until 1972.

However, another of the Allison stories appeared in the February 1934 issue of Weird Tales; and boy, is it a cracker! In The Valley of the Worm Allison recalls his incarnation as the Aryan barbarian Niord; and tells of the mighty Saga of southward drift that ended in the events that were to reappear in ‘guises wherein the hero was named Tyr, or Perseus, or Siegfried, or Beowulf, or Saint George.’

As has been pointed out by others, in less than two dozen pages Howard tells a story that many writers would have spent a volume on at the very least. The excellent Howardian commentator Rick McCollum has also pointed out how it pulls together most of REHs themes in an essay that was subtitled…well, A Gathering of Howard’s Essential Creative Themes *. He lists these as: ‘Racial Drift’; ‘The Picts’ (in Howard’s usual idealized take on his favourite people); ‘Reincarnation’; ‘History’; ‘The Physical Superiority of the Barbarian’; ‘The Moral Superiority of the Barbarian’ (as you can guess, very idealized!); ‘Bloodshed and Battle as a Commonplace Event’; ‘Hate and Revenge’; Lost Civilizations’; ‘Unnatural Enemies’ (which in this case definitely takes us into the realm of Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos); ‘One Strong Man Against All Odds’; ‘Beneath the Earth Lurks Horror’; and ‘Serpents and Apes’.

As you can see, a pretty exhaustive list that Mr. McCollum handles well. And since he also shares my taste in a favourite, quite demented passage from Howard and which appears in this story, I quote it here:

“We came into that brutish hill country, with its squalling abysms of savagery and black primitiveness. We were a whole tribe marching on foot, old men, wolfish with their long beards and gaunt limbs, giant warriors in their prime, naked children running along the line of the march, women with tousled yellow locks carrying babies which never cried – unless it were to scream from pure rage. I do not remember our numbers, except that there were some five hundred fighting men – and by fighting men I mean all males, from the child just strong enough to lift a bow, to the oldest of the old men. In that madly ferocious age all were fighters. Our women fought, when brought to bay, like tigresses, and I have seen a babe, not yet old enough to stammer articulate words, twist its head and sink its tiny teeth in the foot that stamped out its life”.

Top that one, George R. R. Martin!

Gods of the North appeared not in Weird Tales but in The Fantasy Fan for March, 1934; and the reason for this is that it was rejected by Farnsworth Wright when it was submitted under its original title of The Frost Giant’s Daughter. On this occasion, however, I believe that most erratic of editors was correct. Had he accepted this grim tale of the Northern ice-fields it would have become the second published Conan story – and, as I mentioned at the opening of this article, to my mind it just works better with the way they did appear. There is also the very problematic sexual content here

In any case, barring the change in Conan’s name (to Amra of Akbitana!) it is only very lightly rewritten and takes recognizable place in the Hyborian Age. To all intents and purposes, it is a Conan story.

And yet another Conan tale rounds off this fine volume.

Shadows in the Moonlight saw publication in the Weird Tales issue of April, 1934; and this time I really do take issue with Wright’s interference. God knows what possessed him to throw out Howard’s excellent and robust original title – Iron Shadows in the Moon – and replace it with this anemic Mills & Boon outtake.

Here we find Conan the lone survivor of the Hyrkanian massacre of the Free Companions, a bandit group that he has been raiding the borders of Turan in company with; and by the end we leave him as the captain of a Red Brotherhood pirate ship of the inland Vilayet Sea. It is another wonderfully atmospheric piece and Howard draws his Isle of Iron Statues so skillfully that we feel as if we have trod through those forests and ruins right in the company of the Cimmerian and the lovely Olivia of Ophir.

And in the Introduction, James Reasoner gives this interesting snippet of information, which I was unaware of:

“…although published in the April 1934 issue… [it] was actually written over a year earlier and is the first in a sort of series-within-the-series, in which Conan and some beautiful wench that he has rescued from death (or a fate worse than) stumble upon a lost city and confront an ancient evil that lurks there.”

* McCollum is also the author of one of my favourite essays on REH: ‘The Frost Giant’s Daughter: a Deeper Look’. This one is revised and along with ‘The Valley of the Worm: An Analysis’, both are reprinted from their original REHUPA outings and appear in James van Hise’s irreplaceable The Fantastic Worlds of Robert E. Howard.

Published by Wildside Press.

Next: Gardens of Fear.

Recent Comments