The Klan and the Nazis Head for Massachusetts: Marblehead: A Novel of H. P. Lovecraft

By Richard A. Lupoff

“Marblehead was of particular interest. H. P. loved the untrodden paths and would try to find them, always seeking the weird, the uncanny and the unusual.”

–Sonia H. Davis

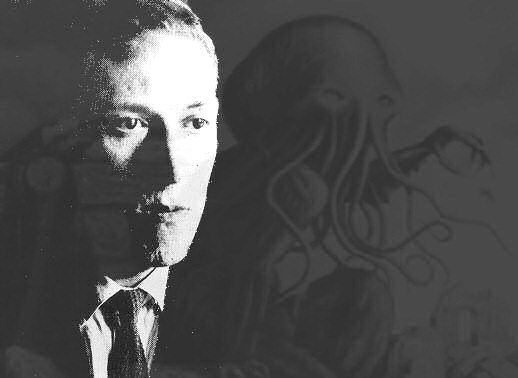

It’s a little sobering to think that I have been fascinated by H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937) and Robert E. Howard (1906-1936) for the guts of forty years now. They were the most popular fantasy writers of the Golden Age of pulp magazines in the ‘20s and ‘30s, contributing in the main to the famous Weird Tales publication. When I discovered them in the ‘70s they were enjoying something of a renaissance, having been at one point almost certain to go out of print and remain that way. It’s true that many of the printings back then were textually unsound, especially as regards Howard. Today, it is possible to find almost anything ever written by them and in its purest form (although it will be many years before all of Lovecraft’s astonishing correspondence sees the light of day. It won’t be in my lifetime and that’s for sure.)

Although they never met, Howard of Texas and Lovecraft of New England kept up a steady stream of letters to each other over half a dozen years. And a fascinating and rich vein of printed gold they are in their own right. The two men were almost diametrically opposed in their views and yet I doubt that some of their tales would have been as good without the influence of each on the other.

In 1936, following Howard’s suicide at the age of thirty, Lovecraft commented: “I value that correspondence as one of the most broadening and sharpening influences of my later years. We were constantly debating sundry historical and philosophical points, and through these arguments (as well as through many passages of sheer description) I gained a much clearer perspective on the various phases of history than I would ever have had otherwise.”

Oddly, whereas I’ve often wished that through some magical time travel I could go back to the small town of Cross Plains as it was and talk to Robert E. Howard I’ve never had the same feeling about wanting to go to Providence to meet Lovecraft. With Howard I could imagine knocking back a great many beers and talking into the night but I’ve always had a feeling that I just wouldn’t like the rather priggish, teetotal, morally superior Lovecraft.

Richard A. Lupoff’s Marblehead, I’m sad to say, doesn’t change that feeling in any way. Indeed, if anything I think that it goes too far and ends up just essentially unfair to its main character. If you knew nothing about him beforehand you certainly won’t like him at the end of this massive mainstream novel. It’s strange, because Lovecraft is Lupoff’s favourite horror writer and in the vast world of really bad Lovecraft imitations he has penned at least two that are interesting: the short stories Discovery of the Ghooric Zone and The Doom that came to Dunwich.

The events take place over the course of the year 1927. It details a fictionalised part of Lovecraft’s life where he has been approached by the real life German propagandist, George Sylvester Vierek—he had conducted an early interview with Adolf Hitler in 1923—and asked to write a book which will detail the coming-together of various fascist and proto-Nazi groups that will change the face of the world. This probably isn’t as far-fetched as it sounds if the manner in which Lupoff portrays post- World War One America is in any way accurate.

Vierek introduces him to the leaders of many of these odd groups, including Dr. Otto Kiep who is the German Ambassador in Washington at the time and Hiram Evans, Imperial Wizard of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, as well as many other interesting characters of the period. They need a name like Lovecraft, since his background is impeccable and there is also the not-inconsequential matter of his anti-Semitic, anti- Slav, pro-Aryan and general all-round racist attitude. The manuscript he prepares is called New America and the Coming World-Empire, a title which tells you it would fit in nicely with the modern internet’s many conspiracy nutters.

Now, Lovecraft’s racism deserves and will eventually get another article all to itself. There is still a lot of nonsense talked amongst well-meaning Lovecraft enthusiasts as to whether he was a racist or not. This is ridiculous as the most cursory glance at his correspondence shows the most awful rants at the cultures of others. Of course he was a racist. They will try to muddy the waters by pointing out that he married a Jewess or that he greatly admired the Jewish Samuel Loveman. He softened up a bit in later years but at this point a racist asshole and a very vile one he most certainly was. As I say, that is another day’s work.

But does Lupoff have to drive the point time and again after it has been made more than amply? Of Hitler, Lovecraft says: “I understand that his wrath is directed against inferior races. Slavs, Jews, the same swarthy mongrels that I despise.” And then there’s the charming: “Once the kikes infiltrate, niggers follow close behind.”

We get it, Mr. Lupoff: he didn’t like Jews, blacks or almost anyone who wasn’t white Anglo-Saxon. But there is so much of this that all you get is Lovecraft the utter bore: a man who lectures all and sundry about colonial architecture; how better off America would be if it hadn’t booted out England; how much he admires Prohibition—although weirdly and unbelievably the teetotal and disapproving Lovecraft is well able to sink a fair amount of booze in this book. Actually there’s an awful lot that is unbelievable about him here. He dives into the Seekonk river, for example, in an attempt to save some poor sod who has been dumped in by bootleggers—complete with cement overshoes. This is a side story that goes precisely nowhere as Lovecraft almost shrugs it off as if it were an everyday occurrence for him. And as for later on and we get Lovecraft in diving gear? Lovecraft—action hero! Oh come on!

But it’s mostly the way in which his wife Sonia Greene behaves like total ditzy doormat that gets me. I simply don’t believe that this astonishingly strong woman would have let him carry on like this at that point in their relationship. [See below.]

Howard Phillips Lovecraft is ultimately portrayed as a boring twat and a bit of a sponger, which would have come as a surprise to his many friends. He may have been mostly broke, but he was very generous when he did have some money—even, as Sonia herself said, often going without so that he could help a fellow writer. He also gave huge amounts of time and encouragement to writers who went on to become famous in their turn. In fact, famous was one thing he never was in his lifetime, no more than Robert E. Howard.

I perked up a bit when the action moved briefly to Cross Plains and a glimpse of Howard. But even this was a let-down, with the 21-year old portrayed as an immature oaf, waving a loaded pistol at a friend for a laugh–another case of complete oversimplification.

There are good things in this book, like the way in which Lupoff brings the year 1927 to life, with his descriptions of food, cars, the first cross-Atlantic flights and the enormously complex politics; but even here I don’t get why it had to be that year, as it means twisting the real life chronology of the characters. With the climax of the Nazi goings on off the coast of Marblehead and inspiring HPL’s famous tale The Shadow Over Innsmouth, 1931 would have worked as well—and wouldn’t have messed with the Howard/Lovecraft correspondence which hadn’t begun in 1927.

I’m also puzzled as to why Lupoff didn’t put in a short epilogue telling us what happened to some of the real-life characters afterwards. For instance, George Vierek was arrested as a Nazi agent and went to prison from 1942-47. He afterwards wrote the book Men into Beasts about prison life, detailing shocking male rape; and Dr. Otto Kiep went on to head the Reich Press Organisation, before turning against Hitler and becoming involved in the famous assassination attempt against him and for which he was executed in 1945.

The manuscript for Marblehead was believed lost in 1976 and this complete edition only appeared in 2006 in a very nice package from Random House. By all means read it for a glimpse into a long gone age, but not as insight into the workings of a very flawed genius.

A Mysterious and Vivacious Ukrainian Exile:

The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft

By Sonia H. Davis

I may not have cared too much to meet Howard Phillips Lovecraft, but one thing is for sure: I would love to have met his wife. Sonia Davis comes across to me as an utterly fascinating person, a strong and able woman and one that it would be very easy for a man to fall for. Existing photographs of her show an attractive lady and call to mind that word that has been used about her: vivacious. Lovecraft needed a good hard boot up his arse for many things he did in life but one of the hardest should have been for not only letting this woman go but for actively driving her away!

The Private Life…is a small 28-page pamphlet published by the specialist Necronomicon Press. It is also essential reading for anyone interested in the short period when Lovecraft—inexplicably—found himself married. I was about to write that it was only for two years but of course, due to HPL’s inability to get his act together regarding almost anything to do with the real world it’s quite possible that they were never divorced at all, meaning that Sonia’s third marriage was bigamous.

This short piece is in Sonia’s own words and reading between the lines I’d say that there was a lot of suppressed anger in her. She talks of one of his friends writing that HPL was living on only twenty cents a day when in fact it was pretty obvious that Sonia was supporting him. And as she says here it’s something that she didn’t mind doing as she believed that she was married to a genius and that this belief would one day be vindicated. Of course, she was right in that respect but I wonder when it finally dawned on her that she would never make a husband out of him. Still, it is rather touching when she writes:

“He was exceedingly caring and sparing of the money I’d give him. The only money he ever spent on me that he had earned was that which he received for the Houdini manuscript [HPL was the escape artist’s ghost writer for a while]… When I insisted that only half the amount be spent for a wedding ring, his own generosity overcame him and he insisted the future Mrs. Howard Phillips Lovecraft must have the finest wedding ring with diamonds all around it even if it took all of the proceeds of that first well-paid story.”

Again, Sonia is too polite to belabour the point but she was treated abominably by Lovecraft’s two aunts, with whom he had previously—and subsequently—lived. Despite having thrown open her home (and her purse) to them, the old snobs looked down on her because she was ‘in trade’. I know the ‘20s were different times but that still makes my blood boil.

On the great mystery of why an anti-Semite would marry a Jew she comments: “I soon learned that he hated [New York] and all its ‘alien hordes’. When I protested that I too was one of them, he’d tell me I ‘no longer belonged to these mongrels’”. Astonishing.

Yet there’s no doubt that she loved him and really tried to make the marriage work. She famously described him as “an adequately excellent lover” and although I know that ‘lover’ had different connotations back then, I find it hard to imagine wrapped tight, buttoned-up HPL in that light under any kind of circumstances. Certainly, she says, he never once told her that he loved her, only that he appreciated her. You were a smoothie, Howard, no doubt about it, he said sarcastically.

Even though it is enormously important for the Lovecraft enthusiast to have this document I would like to know more about her own life, especially after they separated. What little we do know tells us that she was born Sonia Haft Shafirkin in the Ukraine in 1883. (She was by seven years Lovecraft’s senior.) After the death of her father, her mother put her in a school in Liverpool while she went on to America, married again and had Sonia join her in 1892. She herself was married for the first time at the age of sixteen and had a daughter, Florence. There was also a son, who died at three months whilst the husband appears to have committed suicide in 1916.

If ever anyone is able to research her life, which seems unlikely but not impossible at this remove, here is a wealth of material already…not to mention about a hundred unanswered questions.

From the great Lovecraftian scholar, S. T. Joshi, we learn that when she met her future second husband she was in an executive position with a very upmarket clothing store and was earning $10,000 a year—in 1921! This was no ordinary woman. As Lovecraft’s friend Alfred Galpin put it:

“When she dropped in on my reserved and bookish student life at Madison, I felt like an English sparrow transfixed by a cobra. Junoesque and commanding, with superb dark eyes and hair, she was too regal to be a Dostoyevsky character and seemed rather a heroine from some of the most martial pages of War and Peace. Proclaiming the glory of the free and enlightened human personality, she declared herself a person unique in depth and intensity of passion and urged me to Write, to Do, to Create.”

Yes, Lovecraft deserved a very hard kick in the ass indeed!

Sonia’s third husband, Dr. Nathaniel Davis, died in 1946. We know little of her after that but she herself died in 1972 at the age of 89. Perhaps this woman will one day be more than a footnote in Lovecraftian lore. She certainly deserves to be.

Recent Comments