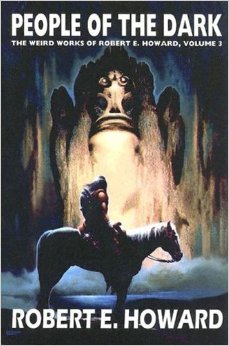

People of the Dark

The Weird Works of Robert E. Howard, Volume 3

Edited by

Paul Herman

Introduction by

Joe R. Lansdale

There’s no other way to put it: the third volume of Robert E. Howard’s collected weird fiction starts with an explosive bloody cracker.

Kings of the Night (Weird Tales, November 1930) is as close to pure Howard as any enthusiast could ask for, as well as being a major leap forward for the young writer on so many levels. It touches on themes close to Howard’s heart whilst allowing him to display what seems to have been an instinctive understanding of strategy in warfare. Had he lived, he would definitely have had a calling outside that of tale-spinning.

I’m not sure why, but despite the sheer perfection of the only other two King Kull yarns to appear in WT –The Shadow Kingdom and The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune – that great but highly contrary editor, Farnsworth Wright, never printed any other Kull pieces in Howard’s lifetime.

Whilst Kull is one of the main actors in Kings it is more usually regarded as the first Bran Mak Morn story. Yet Howard had been writing about the Pictish chief and king since his mid-teens. There even remains extant a fascinating one page-and-a-quarter uncompleted play, written when Howard was sixteen. In addition, the first real tale was also rejected. I’m not sure why, because I’ve always loved the intensity of Men of the Shadows.

At any rate, we can look at Kings of the Night as the first published Bran Mak Morn story; the third King Kull one; and also the first tale of Cormac of Connacht, from whose viewpoint the story unfolds: a rich brew of characters and a very clever crossover of Roman Britain around the first century AD with the Pre-Cataclysmic Valusian Age of Kull.

Deeds Echoing in History

Mak Morn is attempting to unite the Pictish tribes in order to hold back the northward march of Caesar’s troops. For this he needs the help of 300 Vikings, who are being awkward sons-of-bitches who will only agree to fight under certain loaded conditions. To this end his shaman Gonar –who claims direct descent from Kull’s Pictish ally, Brule the Spear-slayer — calls the Atlantean king from the past.

I’ve always loved the character of Bran Mak Morn and deeply regret that we have so few tales. As a Scot myself, I relish this melancholic, romanticized past and find a profound pathos in the fact that Bran knows that – no matter what victory he may win on any particular day – his attempts to hold back Rome are doomed to failure and that he is sure to fall in battle. To my mind, this gives him a stature and nobility to exceed any of Howard’s heroes; and as he is described as being of medium height, ever since seeing Mel Gibson’s brilliant Braveheart years ago, I’ve always imagined the actor in this role.

The action is Howard at his blistering best, as usual seeming to burn off the page; and yet he imbues it all with an eerie quality and superb characterization. Here also is writ large one of his recurring meditations on how intangible all things are:

‘”And then Kull lived despite his many wounds,” said Cormac, “and he has returned to the mists of silence and centuries. Well – he thought us a dream; we thought him a ghost. And sure, life is but a web spun of ghosts and dreams and illusion, and it is in my mind that the kingdom which has this day been born of swords and slaughter in this howling valley is a thing no more solid than the foam of the bright sea.”’

Kings of the Night is –quite simply – a masterpiece.

Stitching a Rich Tapestry

With the next story, The Children of the Night (Weird Tales, April – May 1931), those early readers who had begun following Howard’s work would have realised that –in a manner similar to the great Edgar Rice Burroughs – it was going to be fun to see how many of his stories could be demonstrated as taking place in the same fictional universe. Although it has a contemporary setting, mention is made of a ‘Bran cult’, linking it with the previous Kings of the Night; and thus, of course, linking it with King Kull. There is also mention made of Cthulhu, Yog Sothoth, Tsathoggua and Gol-goroth, making it very much a world of the then blossoming Lovecraft Mythos (Tsathoggua was created by the third member of the Weird Tales greats, Clark Ashton Smith; Gol-goroth is REH’s own contribution). It’s easy to see how 1930s WT readers, seeing these references in the work of more than one writer, could have come to believe that they were links to a genuine, esoteric mythology.

And just to tantalize even farther, he then has one of his characters speak for him in declaring the three master horror-tales to be Poe’s Fall of the House of Usher, Lovecraft’s Call of Cthulhu and Arthur Machen’s Novel of the Black Seal, thus proving that apart from being a great writer he was a man of exquisite literary taste! A bit like Yours Truly, I add modestly.

Six friends gather in the ‘bizarrely fashioned study’ of Conrad, where they thrash out various theories on different racial types. This leads to the first published reference to a tome called the Nameless Cults of Von Junzt, REH’s answer to HPL’s Necronomicon of the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred.

Unexpectedly, the story takes a dramatic twist when a blow to the head sends the narrator back in time to a previous incarnation as a barbarian warrior, Aryara. Without giving anything away, I will say that the conclusion of this short piece is one of the most disturbing in all of Howard’s writing, if not the most disturbing, with its ferocious description of what can only be called rabid racial hatred on the behalf of the now-unhinged narrator.

A very bleak piece, indeed.

The Footfalls Within (WT, September 1931) is another short piece. For those interested in the Puritan adventurer Solomon Kane, however, it is rather a crucial one. Here we see him directly connected to various quasi–historical figures and in addition it should put to rest the ‘racist’ question once and for all, as it is pretty clear that Kane will fight on behalf of anyone who is downtrodden, skin-colour regardless.

I’ve always been very fond of The Gods of Bal-Sagoth (WT, October 1931) which throws together two memorable characters.

Turlogh Dubh O’Brien is an exile of Ireland whilst the giant Athelstane is a wild brawling Saxon outcast who fights with the Vikings. Initially at each other’s throats, the two find themselves in unlikely alliance when swept ashore on the aeons-lost island of Bal-Sagoth, where one of Howard’s most scheming wenches soon has them fighting a city in order to regain her throne for her, the floozy. She’s an outcast too, mind: she was stolen away from the Orkneys when Tostig the Mad raided them. (I just wanted to write that, to be honest. I’ll say it again: ‘when Tostig the Mad raided them’.)

The god Gol-goroth (who we heard mentioned in The Children of the Night) is in this one; and we get some of Howard’s now-familiar philosophy:

“Kingdoms and empires pass away like mist from the sea, thought Turlogh; the people shout and triumph and even in the revelry of Belshazzar’s feast, the Medes break the gates of Babylon. Even now the shadow of doom is over this city and the slow tides of oblivion lap the feet of this unheeding race. So in a strange mood Turlogh O’Brien strode beside the palanquin, and it seemed to him that he and Athelstane walked in a dead city, through throngs of dim ghosts, cheering a ghost queen.”

No doubt about it; it’s a little gem.

Romancing the Stone

And here’s another good one: The Black Stone (WT, November 1931) was Howard’s first full-blown attempt to add to the Lovecraft Mythos. By this time, the Texas Bard and the New England one were involved in one of the most intriguing and often heated correspondences in literary history; and each was learning from the other.

It begins in scholarly fashion, with Howard giving us a full background to the tome mentioned in The Children of the Night:

“It was my fortune to have access to [Von Junzt’s] Nameless Cults in the original edition, the so-called Black Book, published in Dusseldorf in 1839, shortly before a hounding doom overtook the author. Collectors of rare literature were familiar with Nameless Cults mainly through the cheap and faulty translation which was pirated in London by Bridewell in 1845, and the carefully expurgated edition put out by the Golden Goblin Press of New York, 1909… Von Junzt spent his entire life (1795 – 1840) delving into forbidden subjects…”

[It’s worth mentioning that many people at the time were quite taken in by all this, although not to the extent that happened with Lovecraft’s equally fictional Necronomicon, which inspired it. For years antique book dealers were plagued by people trying to source a copy of Necronomicon and as recently as last year I had the dubious pleasure of meeting someone who simply refused to accept that it was invented. [Now, with the proliferation of the odder sites on the internet the whole thing has been given a new lease of life by characters that I consider not to be so much Lovecraft enthusiasts as certifiable nutcases who should probably be sectioned for their own safety; however, I’m always willing to be persuaded. [Lovecraft and Howard would have been amused to find that Necronomicon has taken its place alongside such ramblings as The Hitler Diaries as one of the great literary hoaxes of history – albeit an unintentional one!]The narrator connects a mention in the tome of something called the Black Stone with a poem written by the poet Justin Geoffrey, who ‘died screaming in a madhouse’. This is The People of the Monolith which he had written after a visit to a remote region of Hungary. Rather poignantly, Howard says of him: ‘As is usual with artists, most of his recognition has come since his death’.

Sadly Robert, that is also what happened to you.

Arriving in Hungary we are given a brief lesson on the Turkish Wars, which made me wish that I’d had REH as a history teacher, so gloriously alive do the driest of facts come through his prose. However, this pseudo-academic presentation is about to descend into a nightmare scenario of sadism, masochism, human sacrifice and infanticide in a manner that still startles today – before wrapping up with a suitably shuddersome and bleak ending.

Howard was overly hard on himself with this story, believing that imitation-Lovecraft wasn’t really his style. Of course, it wasn’t; but he paid a very acceptable homage to the Master, a far better one than two from the same period – the rather poor Return of the Sorcerer by Clark Ashton Smith and the utterly crap The Space Eaters from Frank Belknap Long which is, quite frankly, an embarrassment.

I’ve read The Black Stone many times over the years and still get a kick from it. And I would prefer it to all of the Solomon Kane stories strung together. So there.

The Man Who Became a God

The Dark Man (WT, December 1931 ) is another masterwork and again features Turlogh Dubh O’Brien, with a cameo from Athelstane the Saxon. The events here take place before those of The Gods of Bal-Sagoth and it is a more vivid description of the outcast clansman, a stunning portrait of a warrior whose fierce insanity is capable of driving him through situations that would kill a normal, sane man.

From its opening in the snows of a Connacht coastline through an atmospheric journey in open boat to the Hebrides, it grabs the reader by the throat and never lets go. On the way he encounters and carries with him, the statue of a man from centuries ago – a man that we met at the beginning of this volume:

‘”What is this thing?” asked the Gael.

‘”It is the only God we have left,” answered the other somberly. “It is the image of our greatest king, Bran Mak Morn, he who gathered the broken lines of the Pictish tribes into a single mighty nation, he who drove forth the Norseman and Briton and shattered the legions of Rome, centuries ago. A wizard made this statue while the great Morni yet lived and reigned, and when he died in the last great battle, his spirit entered it. It is our god.

‘”Ages ago we ruled. Before the Dane, before the Gael, before the Briton, before the Roman, we reigned in the western isles. Our stone circles rose to the sun. We worked in flint and hides and were happy. Then came the Celts and drove us into the wilderness. They held the southland. But we throve in the north and were strong. Rome broke the Britons and came against us. But there rose among us Bran Mak Morn, of the blood of Brule the Spear-slayer, the friend of King Kull of Valusia who reigned thousands of years ago before Atlantis sank. Bran became king of all Caledon. He broke the iron ranks of Rome and sent the legions cowering out behind their wall.

‘”Bran Mak Morn fell in battle; the nation fell apart. Civil wars rocked it. The Gaels came and reared the kingdom of Dalriadia above the ruins of the Cruithni. When the Scot Kenneth McAlpine broke the kingdom of Galloway, the last remnant of the Pictish empire faded like snow on the mountains. Like wolves we live now among the scattered islands, among the crags of the highlands and the dim hills of Galloway. We are a fading people. We pass. But the Dark Man remains – the Dark One, the great king, Bran Mak Morn, whose ghost dwells forever in the stone likeness of his living self.”’

I feel that it is worth quoting this powerful, evocative passage in full, as it illustrates just how deeply Howard has become immersed in his own growing mythos over a very few years. He was still only 25, but there was a richness to the texture of his work that you would have been hard pressed to find in writers twice his age, who had the supposed advantage of living in a teeming metropolis rather than the one-horse town of Cross Plains, Texas.

With The Thing on the Roof (WT, February 1932) he returns to the Lovecraft Mythos, although by now of course his own was being incorporated into it. This is an exceedingly slight work but holds the attention well as we learn of the Temple of the Toad in Honduras and hear some more of Von Junzt’s Nameless Cults and the mad poet, Justin Geoffrey.

From internal evidence I feel it’s safe to have the narrator as the same one who told us of the Black Stone in Hungary. These events, however, are obviously of an earlier vintage.

After this treasure-trove of goodies it’s a bit of a let-down to come to Horror from the Mound (WT, May 1932). Although it’s set in the southwest Texas of Howard’s time and contains interesting lore on the Spaniards who crossed there in bygone centuries, I find it a very run-of-the-mill vampire story. Others differ, though, as we see with Joe R. Lansdale’s introduction to this volume:

“This collection contains many fine tales. One of my favourites is ‘The Horror from the Mound’. I’ve read it many times, but when I first read ‘The Horror from the Mound’, I was certain I had never read a horror story quite like it. It wasn’t the usual tale of a monster and a hapless protagonist, but that of a Western hero confronted with a problem, and like all true Western heroes, he had to just go out and do what he had to do, which was face off with the thing and try to defeat it.”

To each, their own.

The Coming of Conan

As we reach the end of the current volume I’ll just mention that this one is light on Howard’s poetry, containing only two pieces. By now it had hit him that Farnsworth Wright would only publish one work from a writer in any given issue; and since –unlike Lovecraft, who had his own peculiar ideas about how so-called gentlemen behaved — REH was writing primarily to make money, it didn’t really suit him to continue to submit the shorter poetical works rather than the larger-paying stories.

With the debut of Howard’s legendary barbarian of Cimmeria only six months away, it may come as something of a surprise to find that he was first mentioned in the magazine Strange Tales in June, 1932, rather than the one that would become his spiritual home. This Conan, however, is not out of pre-history, but is in fact an ancient Irish reaver.

A sequel of sorts to The Children of the Night, as with its predecessor, this is an Arthur Machen-inspired short story. It is also something of a Reincarnationist love triangle. John O’Brien has followed his rival Richard Brent into the intriguingly named Dagon’s Cave in England with every intention of murdering him in order to claim the heart of the lovely Eleanor Bland.

However, a blow on the head sends him back to a period in Time (sound familiar?) where, as Conan of the reavers, he battles the regressed remnants of the Little People. The two other characters are also there as members of a tribe of Britons that Conan’s comrades have attacked.

In both the incarnations of Conan and as O’Brien – I’m so tempted to make a joke about a certain talk show host – this is one of Howard’s more reprehensible ‘heroes’, even if he does finally redeem himself. It’s not a story I care for overmuch. Even the fight scenes are unusually weak. And as for the groan-worthy ‘romantic’ modern dialogue, the less said the better.

I will quote this, though, as it has a bearing on one of REH’s later, best and most important stories, which we’ll read in the next volume:

“The Black Stone! The ancient, ancient Stone before which, the Britons said, the Children of the Night bowed in gruesome worship, and whose origin was lost in the black mists of a hideously distant past. Once, legend said, it had stood in that grim circle of monoliths called Stonehenge, before its votaries had been driven like chaff before the bows of the Picts.”

And there we take our leave. It’s a pity that Volume 3 started out so strongly and stayed so consistently fine, only to end with this rather poor outing.

However, in the naming of its protagonist that story looks forward to the next collection and the introduction of the character that would bring – if only posthumously – lasting fame to Robert E. Howard: the barbarian called Conan of Cimmeria.

Recent Comments