This piece was originally posted on Dec. 26 2012.

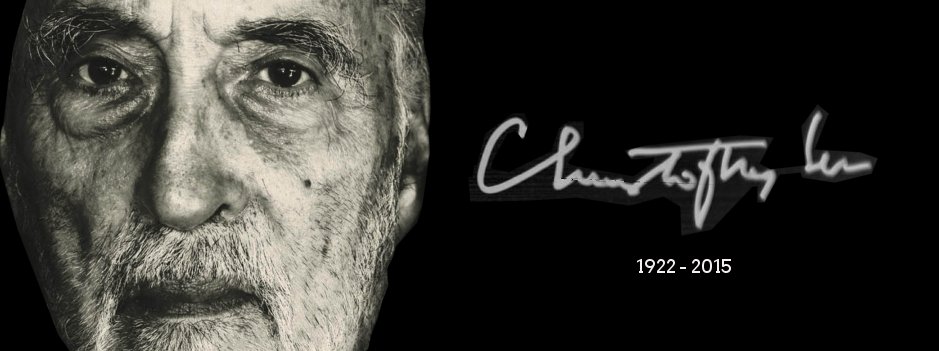

With respect – Christopher Lee / Cinema Legend 1922 – 2015

Inside the Wicker Man

The Morbid Ingenuities

By

Allan Brown

“It is a film about sacrifice which was itself sacrificed. It is also a film about the life force; it has been hacked, slashed, buried, written off and lost but it continues to live; indeed it refuses to die.”

—-Introduction.

I love that phrase: the Morbid Ingenuities. Somehow you think of it with capital letters. Instinctively, I knew what it meant, even though I wasn’t really sure what it meant. If that doesn’t make much sense to you then don’t worry because it doesn’t make much sense to me either; and not because I’ve had a dose of unintelligible Eastern mumbo-jumbo. The philosophy at hand here is much closer to home. It is much more Western and much more earthy and very much more pagan. It is the strange world of the Wicker Man. In Allan Brown’s book Inside the Wicker Man you learn just how strange anything to do with that world and with getting the film of The Wicker Man out really was.

This is the 1973 version that Brown is dealing with, not the misguided Hollywood remake with Nicholas Cage, which should tell you all you want to know about how that one turned out. Suffice to say that the real one began life as a story that was written by Anthony Schaffer, with his friend and partner of the time Robin Hardy set to direct and a very interested and enthusiastic Christopher Lee chomping at the bit to star in it.

It deals with a straight-laced ‘Christian copper’ on the mainland of Scotland who travels to the private island of Summerisle in order to investigate the disappearance of a child; but who finds instead that he is being played with by an entire village of modern-day pagans whom he can scarcely conceive of as existing in the 20th century.

For a film dealing with such subject matter there’s a supreme touch of irony worthy of the Old Gods themselves that everything about it seems almost to have been cursed from the beginning.

“The film was born of a shotgun wedding between John Bentley (aka Pretty Boy Bentley). A young, flamboyant tycoon who had purchased the ailing Shepperton Studios and Britain’s all-powerful film unions, who had got the notion under their caps that Bentley was set to asset-strip and close the studios down. To placate them, Pretty Boy ordered that a film be put into production immediately. As it happened, British Lion, who used Shepperton, had a script on the starting blocks: The Wicker Man. It was set, however, on the west coast of Scotland at the height of spring, yet production could not commence until the late autumn. Bentley insisted British Lion proceed anyway. The often flimsily dressed cast were forced to endure long shoots in agonizing headwinds, sometimes with ice-cubes in their mouths to prevent their breath showing on camera. Trees were hung with artificial apple blossom. The madness had begun.”

Indeed, the whole making of, production of and taking of the movie to America is so involved and at times so unbelievable that only a real Wicker enthusiast could have the patience to follow every strand, watching at times no doubt helplessly as those strands unravelled and went off in another direction completely. Wicker fans and admirers of film restoration in particular are fortunate to have one such character in Brown. There is no doubt of how keen he is on this project and it doesn’t hurt that he has a clear and concise writing style as well as a sense of humour, which he no doubt needed at times. (Although he certainly seems to hold a hell of a grievance against William Friedkin’s The Exorcist.)

By the time that the film was completed and ready for release there seemed to be executive assholes ready to hate the film, come what may. Michael Deeley, managing director of British Lion took a pair of scissors to it immediately, cutting away like a lunatic until the print that I saw originally back in 1973 was only 84 minutes long and playing as the bottom half of a double bill—with the brilliant Don’t Look Now from Nicholas Roeg, it must be said. So that was alright!

Yet I and thousands like me sensed a really fine film even in its butchered state and this led to some fans lobbying for years in order to have the film restored to its original version, something that proved far harder than it should have. In touching on “the continuing thorny issue of the film’s missing footage” Brown comments accurately: “It is sobering to reflect that Abel Ganz’s silent masterpiece Napoleon was reconstructed more than sixty years after the film was made, or that the infamous snails-or-oysters scene from Spartacus was restored thirty-five years after it was censored on the grounds of decency.”

‘A Classic film about Cultism… at the Centre of its Own Cult’

Most of the principles involved in The Wicker Man seem to have given of their time generously in the writing of this book. Edward Woodward, who played the policeman Howie, is very entertaining although one suspects that some of his anecdotes should be taken with a lot of salt. Maybe it’s just that so much time has passed. And as for Christopher Lee, who played the ‘enlightened’ pagan Lord Summerisle, his endless loyalty to and promotion of the film are a complete credit to a busy actor. It surely has gone far beyond anything he might have been expected to do. On top of that he has a pretty good line in conspiracy theories regarding what almost seems to be the wilful destruction of the film. Sadly, as much as I love conspiracy theories I suppose that Hardy and Schaffer are probably right in putting it down to the sheer bastardly bad luck the film endured from the first day.

In the final analysis, if such a thing is possible with a work as complex as this one, it probably comes down to the clash between two kinds of fundamentalism (and how appropriate that seems for our own strange days). On the one hand we have Howie representing extremist Christianity and on the other Summerisle with his extreme version of Paganism. I’ve always liked Howie’s utter indignation at Summerisle espousing pregnancy induced by jumping through bonfires and how this conflicts with the belief in Jesus.

Summerisle quite rightly puts on a baffled face. After all, wasn’t Jesus the son of a virgin, conceived by a ghost?

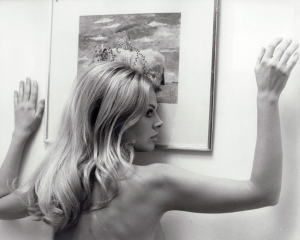

There are wonderful anecdotes throughout and it’s always great to see anything from the late Ingrid Pitt. Britt Ekland, on the other hand, seems to have a strangely inflated sense of her own importance and has pretty much disassociated herself from the film completely over the years. She also seems to retain quite a touch of the Diva about her.

At the time she spoke in rather non-endearing terms of the place that she was filming in, Newton Stewart in Scotland: “…had to be the most dismal place in Creation…one of the bleakest places I’ve been to in my life—and I’ve been around quite a bit in my time. Gloom and misery oozed out of the furniture and I walked into the hotel looking as though I’d stepped off the cover of ‘Vogue’.”

Gosh. Good for you, Britt. Take a swipe at the peasants who should have been on their collective knees just because you were once shagging Peter Sellers and was now at this stage shagging Rod Stewart. As for that bit about “I’ve been around a bit in my time.” You don’t have to remind us.

How to win friends in a country that has welcomed you, indeed!

Odd thing is that I think that that Ekland was a bit tough on herself as well as everyone else. She seems to believe that her Scottish accent was dubbed and yet in the audio-commentary on the DVD that I have Lee, Woodward and Hardy all seem to agree that the only thing that was dubbed was her singing. And to be honest her Scottish accent was as good as the smorgasbord of accents we got here. So lighten up and stop being a bitch, Ekland.

Woodward tells a terrific story about Christopher Lee that strikes me as true. I’ve always suspected that Lee could talk for England—and as a long-time fan I could listen to the guy all day. However, I’ve also had suspicions that he might be able to go on a bit. Over to Woodward:

“One morning Diane Cilento and myself were having breakfast in the hotel when Christopher walks in, sits down and begins to tell a story about a golf tournament he’d been invited to in the Middle East. He tells us about this in great detail for about ten minutes when quickly the transport turns up and we have to leave, with Christopher stemmed in mid-flow. Three days later, I’m on set at Burrowhead, freezing to death, dressed in a shift, waiting for the camera to roll, so I can get back to the hotel and have a large whisky, standing talking to Diane. Christopher strolls over—and with no introduction picks up his golf story exactly the point he left off, as if there had been no interruption. He was like a tape recorder. It was bizarre. Nobody else can tell a story like Christopher Lee.”

On my audio commentary Lee says that he doesn’t recall drinking in the local hotel with the cast. I think that I can probably guess why. Never mind, he’s still one of the all time greats.

As to that wonderful subtitle, it came by way of an unconnected interview that the author was doing with one George Steiner, Weidenfeld Professor of Comparative Literature at Churchill College, Cambridge. As he takes his leave of the academic he mentions that his next assignment is to cover a conference in Liverpool on the theories concerning the assassination of JFK.

“The professor was aghast at the notion of such an event. In the 1940s, his family had escaped the Warsaw ghetto. Steiner had himself written frequently on the Holocaust, and on how preamble is the barrier between civility and barbarity. This was not someone to tolerate the notion that one man’s death could become another man’s recreation. Nor did he regard the conspiracy buff’s averred desire—to expose the ‘real’ killers—as anything but bloodlust masquerading as piety. Steiner found the idea of such a conference deeply appalling. But when he spoke his voice was bathed in pity: ‘These poor fools,’ he said, his head shaking slowly. “It is easy to feel sorry for someone consumed by such…morbid ingenuities’.

“Morbid ingenuities. The phrase has gnawed at me since. With breathtaking concision, it seems to capture a range of mind-sets and reflexes, habit and actions. So much of what confronts us now is morbid in nature, and so many of the ways this morbidity is furthered displays unmistakable ingenuity.”

This is an admirable book; but if there is one thing that I wish it had delved into a little more it is on the many who long ago crossed the line from simply being enthusiasts of one particular movie and at some stage moved into fanaticism where, as one fan put it, the world of the movie had become more real than the world we live in.

Still, that is their thing and who am I to judge, a man with his own obsessions. And in the end, whether we like it or not we will all one day have to keep our own appointment with the Wicker Man.

Inside the Wicker Man is by Allan Brown and published by Sidgwick & Jackson, an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

The copy I have is from Studio Canal and is excellent value. It contains the theatrical release and the Director’s Cut, as well as numerous extras. If you have even a mild interest in film restoration—or even just great film! — this is essential for your collection. Or is that just my own morbid ingenuity kicking in?

Here’s the famous Fire Leap scene where Summerisle points out the obvious to the Christian Copper.

Recent Comments