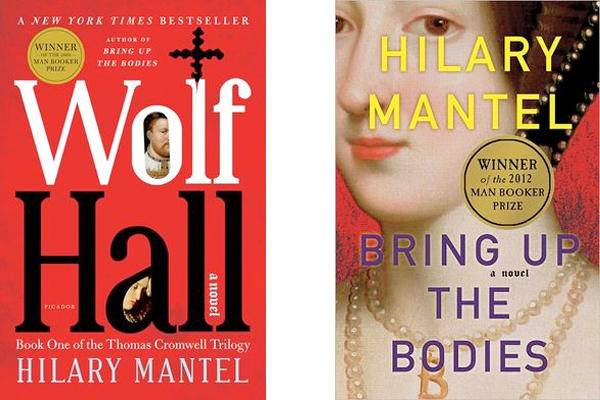

Life on Planet Booker:

Wolf Hall

“Thomas More comes to Austin Friars. He refuses food, he refuses drink, though he looks in need of both.”

This is on page 351 of the hardback edition of Hilary Mantel’s Man Booker Prize-winning 2009 novel Wolf Hall. I’ve just read that sentence and closed the book, knowing that little would ever entice me into opening it back up. I don’t care whether or not Thomas More ever eats or drinks again; and further, I couldn’t care less whether the novel’s main character Thomas Cromwell will ever eat or drink again either. Enough is enough and whilst I hate putting any book down unfinished—after all, a writer has put a lot of effort into it—I’m also aware that there are far too many other books in the world that I really want to read and that I’m not getting any younger. And oh hell, there are still 300 pages left to go and Life is just too damned short.

I sometimes wonder what planet Booker Prize judges are living on because it’s certainly not the same one as most of us. Maybe it’s the one where Nobel peace prizes go to evil old warmongering party-goers like Henry Kissinger; the same one where Oscars get handed out to bore-a-thons like Lincoln. I haven’t really paid much attention to the Booker Prize since J. G. Ballard’s brilliant Empire of the Sun hilariously lost in 1984 to Hotel du Lac. Not that I have anything against Anita Brookner’s bleak little novel but, come on… seriously?

You wouldn’t think that you could go far wrong with Wolf Hall, though. I mean, it covers the exciting historical period in which Henry the VIII was attempting to show that his marriage to Catherine of Aragon didn’t actually exist as he was far more interested in getting the leg over Anne Boleyn. Anne, however, wasn’t having any of that nonsense thank you very much without him putting a queen-sized sparkler on her finger first. Some women are like that. Of course, this brought him into conflict with Pope Clement VII who quite reasonably supposed that since the marriage to Catherine was twenty years old then it most certainly did exist. Henry had some odd ideas, though, to put it mildly. Here are Cardinal Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell discussing them:

“ ‘Well, Deuteronomy. Which positively recommends that a man should marry his deceased brother’s wife. As he did.’ The cardinal sighs. ‘But he doesn’t like Deuteronomy.’

“Useless to say, why not? Useless to suggest that , if Deuteronomy orders you to marry your brother’s relict, and Leviticus says don’t, or you will not breed, you should try to live with the contradiction, and accept that the question of which takes priority was thrashed out in Rome, for a fat fee, by the leading prelates, twenty years ago when the dispensations were issued, and delivered under papal seal.

“ ‘I don’t see why he takes Leviticus to heart. He has a daughter living.’

“ ‘But I think it is generally understood, in the Scriptures, that ‘children’ means ‘sons’.”

You see the trouble that auld Bible yoke causes? Wouldn’t it have saved us a lot of grief over the years if it had never been written? That and the Koran. And Norman Mailer novels.

As a matter of fact, I love this kind of theological angels-on-the-heads-of pins debate; and in fact for the first hundred or so pages of Wolf Hall I thought this was going to be great. There is some lovely imagery (‘He will remember his first sight of the open sea: a grey wrinkled vastness, like the residue of a dream’) and in fact I’ve used some memorable lines to bookend an article on the sister blog to this one— Suffer the Little Children on www.charleybrady.com . I also liked the idea of making Cromwell a hero. I knew little of him outside of Robert Bolt’s brilliant play A Man for All Seasons and oddly for me I can’t recall much of him in Shakespeare either; but the concept of making him the polar opposite of the way in which Bolt portrays him seems sound. And Mantel does the same thing with Thomas More. Here he is an utterly slimy little creep whereas he is nobility and courage personified in the play, and portrayed so brilliantly by Paul Scofield in Fred Zinneman’s powerful film version.

Eventually, though, it just seemed that Mantel was droning on and on to no great effect. She uses the irritating device of putting ‘he said’s’ all over the place in a manner which is sometimes confusing and often seems to be just damned bad writing. I think that it’s supposed to make it all more intimate, but in fact I always felt distanced and rather unmoved by the events in the story, even some deaths which are meant to be shocking.

As I say, in the end I’m glad that I’ve abandoned it; I don’t feel as if I’m going to be missing anything and in fact I feel ridiculously relieved.

Now it will probably be made into a movie and win ten Academy Awards and the Nobel Prize for Art. And Literature. Stranger things have happened.

Recent Comments