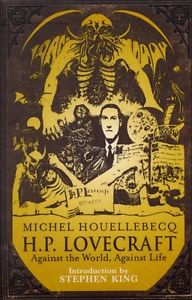

H.P. Lovecraft:

Against the World, Against Life

‘Of course, life has no meaning. But neither does death. And this is another thing that curdles the blood when one discovers Lovecraft’s universe. The deaths of his heroes have no meaning. Death brings no appeasement. It in no way allows the story to conclude. Implacably, HPL destroys his characters, evoking only the dismemberment of marionettes.’

Or:

‘At the intersections of these channels of communication, man has erected giant ugly metropolises where each person, isolated in an anonymous apartment in a building identical to the others, believes absolutely that he is the center of the world and the measure of all things. But beneath the warrens of these burrowing insects, very ancient and very powerful creatures are slowly awakening from their slumber. During the Carboniferous age, during the Triassic and the Permian ages, they were here already; they have heard the roars of the very first mammals and will know the howls of agony of the very last.’

I wonder does writer Michel Houellebecq himself realise what a despairing, aching howl into his own personal void this sparse, ninety-page essay comes across as?

Essay? Rather, this is a blistering and uncompromising love-letter to a writer that he both adores and feels an enormous affinity with. But I doubt that he would take kindly to the suggestion that he himself is despairing. I suspect that the apparently coolly arrogant Mr. Houellebecq sees himself as being somewhat above the affairs and fears of ordinary mortals (although it’s entirely possible that this is simply a role that he enjoys playing); and in that he does indeed perhaps share a trait with H. P. Lovecraft.

I doubt, though – it’s just a feeling — that the French provocateur is as fundamentally likeable as the Pale Prince of Providence was. Although in fairness he has a lot to be arrogant about: throughout this astonishing critique of Lovecraft’s work and self he is more often right than wrong. And his writing is always superb.

A No-Longer Well-Bred Racism…

I’m going to skip over minor irritants such as stating that HPL never referred to money in his stories or that he only mentioned women twice. That’s not terribly important and certainly not worth arguing about. What is surprising, given Houellebecq’s reputation – probably deserved – as a misogynist, is that he considers the serious question of Lovecraft’s appalling racism so fairly, with such balance and with really penetrating perception.

It’s probably easy to forget, when one has spent perhaps too much time in overly-close proximity to HPL’s writings, that his distaste towards anybody not of Anglo-Saxon blood was really no more than the aloofness of his particular class. At least, until his fateful two-year stay in New York City, where he seems to have become almost truly demented. Indeed, it was when recently reading his collection of letters from NY in 1924 – 1926 that I thought that he might actually have been clinically mad at times.

Houellebecq writes:

‘Disdain is not a productive literary sentiment; generally, it results only in well-bred silence. But Lovecraft was forced to live in New York, where he came to know hatred, disgust, and fear, otherwise stimulating sentiments. And it was in New York that his racist opinions turned into full-fledged racist neurosis. Being poor, he was forced to live in the same neighborhoods as the “obscene, repulsive, nightmarish” immigrants. He would brush past them on the streets and in public parks. He would be jostled by “greasy sneering half-castes,” by “hideous negroes that resemble gigantic chimpanzees” in the subway. And in the long lines of job seekers he came across them again and realized to his horror that his own aristocratic bearing and refined education tempered with his “balanced conservatism” brought him no advantage. His currency was worth nothing here in Babylon; here wiles and brute force reigned supreme, here “rat-faced Jews” and “monstrous half-breeds skip about rolling on their heels absurdly.”

‘This is no longer the WASP’s well-bred racism; it is the brutal hatred of a trapped animal who is forced to share his cage with different and frightening creatures.’

By now the language had actually reached the heights that he would use in the tales written in the last ten years of his life, after his return to Providence in 1926. (‘Monstrous and nebulous adumbrations of the pithecanthropoid… could not by any stretch of the imagination be called human…gelatinous degenerate fermentation…) And with his growing admiration for Hitler comes the most disturbing passage in Houellebecq’s brilliant essay:

‘The longer Lovecraft was forced to remain in New York against his will, the greater his repulsion and his terror, until they reached alarming proportions. Thus he would write to Belknap Long, “the New York mongoloid problem is beyond calm mention.” Further on in the letter he declares, “I hope the end will be warfare…” In another letter, in a sinister presage he advocates the use of cyanide gas.’

Chilling, indeed.

The Fury of a Demented Opera

With the dissolution of his bafflingly ill-advised marriage and his departure from New York for a return to New England, sanity returned.

Well, somewhat.

Yet without that crucial two-year period there would have been none of what Houellebecq calls the ‘great texts’. In a memorable description he refers to the earlier, shorter pieces as ‘anterior texts; where we can see the methods of his art coming to life one by one, like musical instruments, each attempting a fleeting solo before plunging together into the fury of a demented opera.’

Without the skyscraper-lined canyons of NY there would have been no dripping, Cyclopean corpse-city of R’lyeh and its tomb where dead Cthulhu lies dreaming. Out of Lovecraft’s agony and despair was born a mythology and a body of work that seems destined to survive the centuries. I have no doubt that in 2116 his ‘great texts’ will still be discussed and pored over.

Unlike Houellebecq, I think that Lovecraft would have liked life a lot better – at least he wouldn’t have hated it as much as he did – if he had just had access to more money. (Well, who wouldn’t, sez you.) He had a deep curiosity – if not for his fellow humans – about the world; and within the limits of his purse he travelled far more extensively than this writer gives him credit for. On one thing he absolutely nails it, though:

‘What is indisputable is that Lovecraft, as it is sometimes said of boxers, was “full of rage.” But it must be stated unequivocally that in his stories the role of the victim is generally played by an Anglo-Saxon university professor who is refined, reserved and well-educated. Someone who, in fact, is rather like himself. As for the torturers, servants of innumerable cults, they are almost always half-breeds, mulattos, of mixed blood, among the basest of species… So the central passion animating his work is much more akin to masochism than to sadism; which only underscores its dangerous profundity…’

And here, I would argue, Houellebecq himself is at his profoundest. In the full argument, there is a great deal to ponder – but I would surmise that just as without New York there could be no R’lyeh, so without HPL’s fear of half-castes there could be no Innsmouth Look, no shadow hanging over that rotting Massachusetts town.

_______________________

I took this down from the shelf to re-read because a young acquaintance had expressed a wish to find out ‘what all the fuss was about’ regarding Lovecraft. And while I would argue that a month before his wedding isn’t the best time to be entering that world, this package is the perfect way in.

Although as I said, the actual essay is only about ninety pages, there is a fine introduction by Steven King entitled ‘Lovecraft’s Pillow’ and which addresses some of the problems that most people might have with Houellebecq – because he is delightfully and often maddeningly opinionated.

Also reprinted are two of the truly ‘great texts’: The Call of Cthulhu and The Whisperer in Darkness.

All in all, a fine introduction to the man himself.

- P. Lovecraft:

Against the World; Against Life

by Michel Houellebecq

Translated from the French by Dorna Khazeni

This edition published in Great Britain in 2008 by Gollancz

An imprint of the Orion Publishing Group

Recent Comments