A Steve McQueen Double:

The Getaway

&

Papillon

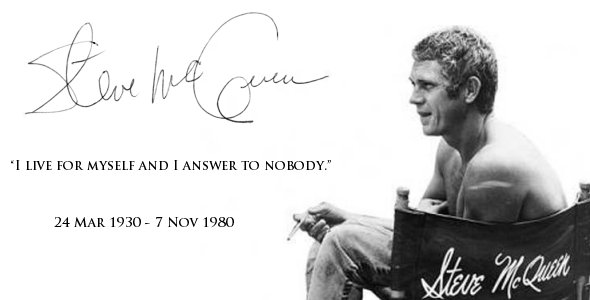

By the mid-seventies Steve McQueen had become, along with Clint Eastwood, the very embodiment of laid-back heroes and antiheroes. He was a major star and in fact so efficient was he in the persona that he created for himself that it was only following his death from cancer at the age of 50 that film fans sat up, re-evaluated him and slowly let it dawn on them that he was—within the limitations of that persona—a damned fine actor. Certainly, it was impossible to take your eyes off him when he was on the screen. This is the guy who out-acted Dustin Hoffman, for Pete’s sake!

In the following piece I’m going to leave out the man’s real-life personality. It doesn’t seem to have been too pleasant; but if we were to judge every actor by how nice they were we wouldn’t be watching too many movies, that’s for sure. McQueen was an alpha male off-screen as well as on, and even though that may hit the notes with teenage boys it doesn’t always make for someone who is good company.

In 1972, at the height of his popularity, McQueen came in contact with another man whose name was becoming a by line for machismo. In fact, McQueen and the great film director Sam Peckinpah had come close to working together years before, in 1964 on The Cincinnati Kid. Unfortunately, in a sequence of events too ludicrous and lengthy to go into here, Peckinpah was fired after only a few days and found himself virtually unemployable for several years to come.

Now, following three terrific films in a row—The Wild Bunch, The Ballad of Cable Hogue and Straw Dogs—Peckinpah had become what was at that time almost unheard of: a director who was known by name to the general public.

Perhaps in reaction to the controversy surrounding Straw Dogs, Peckinpah was ready to take on something a little quieter. This coincided with Steve McQueen looking for material that would let him portray someone other than a guy who looked good riding a motorbike or driving a car at high speed. The result was a small masterpiece, Junior Bonner, the tale of an ageing rodeo rider and his father, a man who has never grown up. In its way it is as much about men born out of their time as the director’s previous outings Ride the High Country and The Wild Bunch. To my mind it is one of his best films and showcases one of McQueen’s finest performances. Unfortunately the critics didn’t do it any favours and the public stayed away in droves.

Still, despite the fights—which on occasion became physical as you would pretty much expect from these two—McQueen wanted to work with Peckinpah again. He owned the rights to a Jim Thompson novel, The Getaway, and he brought Peckinpah on board to direct it. This was the first time that the director was doing something purely for the money, but being a professional it is still an excellent genre film and even has flashes of brilliance. Thompson’s book is as black as Hell at midnight and would probably have been unfilmable at that time. Enter a young scriptwriter, who was beginning to get a name for himself, to tidy it up and make it a bit more palatable for the sensitive audience. This was Walter Hill, who was on the verge of having a great run himself as a director with The Driver, The Warriors, The Long Riders and the strangely disconcerting Southern Comfort.

The Getaway (1972) is the story of Doc McCoy, who has just spent four years in prison for bank robbery. He is pretty much broken as the film begins and asks for his wife Carol (Ali McGraw) to organise his release by way of the crooked Sheriff Jack Beynon, played to smug perfection by Peckinpah regular Ben Johnson. The price is Carol in bed with him and oh, by the way, the good Doc has to rob another bank for him.

McCoy isn’t a very likeable character, never less so than in his dealings with Carol. He knows damned well what his wife has had to do in order to secure his release and yet he never stops bitching and moaning about it. He even slaps her around (well, it is a Jim Thompson novel so I suppose she gets off lightly). Also, in one scene he grabs a little boy by the arm and not only threatens to break it but looks as if he means it. In a hilarious touch, as soon as he is let go the kid squirts him on the back of his prison haircut with a water pistol.

The bank robbery, of course, goes pear shaped and Doc and Carol go on the run, making—like many a Peckinpah hero before them—for Mexico.

This may sound very seen-it-all-before but truly, in Peckinpah’s hands, with McQueen’s excellent, brooding performance and an outstanding supporting cast, it has become something of a cult classic. And if you want something to compare it to, try the hideous, appalling remake with Alex Baldwin and Kim Basinger.

If it deserves to be seen for just one thing—and this is something that is quite exceptional—it is the credit sequence and the first few minutes of running time afterwards. With only the sound of workhouse machinery dully thumping remorselessly away in the background we skip back and forth non-sequentially, as we see how McCoy spends his endless prison time. We go from work detail to chess game to the making of a model bridge. (A bridge to nowhere?) It begins to seem endless as the machinery chugs away on the soundtrack and we have memories thrown in of McCoy in bed with his wife. With McQueen not saying a single word we can read the despair that is coursing through him until he crumples the bridge to pieces and in a single freeze frame he is leaning forward, ready to give in to the corrupt Beynon. It is filmmaking and acting at its best and rarely has the mechanisation of an artificial world been captured so deftly.

Later, there is another great piece when McQueen silently tracks a con man through a train. He looks as if he is about to explode in his intensity. (I’ve often wondered if this inspired the similar scene with Bruce Dern in Walter Hill’s The Driver.)

In contrast to their previous collaboration The Getaway was an enormous box-office hit, making Peckinpah the highest-paid film director in the world at that point and reasserting McQueen as a top action actor. Indeed, following The Towering Inferno two years later, he would become the highest- paid actor in the world. He was still looking for something that would expand his range, however, and for his next project he turned to something quite different.

l

From Mexico to Devil’s Island

Papillon was a best-selling book by Henri Charrier who was, according to who you listen to, either the only man or one of very few to have escaped from the infamous Devil’s Island in French Guiana. His nickname was Papillon (‘Butterfly’) due to the distinctive tattoo on his chest.

With McQueen on board to play the physically challenging title role he completed a crew with impeccable credentials. The film had been adapted from Charrier’s work by screenwriters Dalton Trumbo and Lorenzo Semple Jr. And was to be directed by Franklin J. Schaffer, who was on a role with three Academy Award-nominated pictures behind him—Planet of the Apes, Patton and Nicholas and Alexandra. McQueen’s co-star and crucial to the film was an actor who had been steadily making a name for himself as a driven perfectionist: Dustin Hoffman, star of The Graduate, Midnight Cowboy, Little Big Man and, indeed, Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs.

McQueen, who didn’t care for being upstaged by anyone else, must have approached acting alongside Hoffman with a fair bit of trepidation. Especially since his role as Degas, the counterfeiter with the diffident manner and the bottle bottom glasses, had all the makings of a scene-stealing character. McQueen needn’t have worried, though. He completely rose to the challenge of Papillon. There is a depth and pathos to his acting —especially in the final half hour—that is wonderful.

He portrays Papillon over a fourteen-year period of imprisonment, where an unimaginable total of seven were spent in isolation; and the overall brutality of the whole system is so utterly dehumanising that I’m literally looking for words to describe it.

As a lifelong Peckinpah fan I’ve seen The Getaway many times over the years; but until yesterday I hadn’t seen Papillon since the mid-seventies when I went to it with my late dad. What strange emotions it brought up. My father loved these kind of movies: another one we saw in the same period was a re-release of The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957). And if you are reading this and old enough to remember, don’t you agree that an evening at the movies was more of a real event back then? Especially a great big epic with real film stars– like Papillon! (No one except nerds like me gave a shit who directed it. I know that my dear old Dad never had a clue what I was on about.) And something that I miss to this day was the sense of occasion and the excited anticipation when those curtains opened.

I had forgotten what a fine film Papillon is, but it was really Steve McQueen’s performance that riveted me. Again, I was reminded of just how much this guy can act without dialogue. I’m not dismissing Hoffman, by the way; Jeez, how could I? He is indeed brilliant as Degas. It’s just that I take it for granted now that he’ll be perfect in anything he does. McQueen, though, is a revelation. And even though I said that these two films were quite different, watching them back to back shows up some coincidental similarities.

Neither film uses as much as a note of music for about the first twenty minutes. In The Getaway we open with McQueen having spent years in jail. In Papillon he is about to.

The first thing we see is a shot of marching boots and that is the first sound we hear. Then the men are introduced with calm brutality to their new existence:

“As of this moment, you are the property of the penal administration of French Guiana…as for France, the nation has disposed of you. The nation has rid herself of you altogether.”

And considering that most of these men will never see a woman again, the use of the feminine is particularly poignant.

When we do eventually hear the first notes of Jerry Goldsmith’s soundtrack they are harsh, almost discordant, designed to jangle the nerves of the audience; and so it remains until Papillon has escaped to the mainland, where he has a brief lyrical interlude with a South American tribe. Startlingly for me, one shot of him hugging a girl in the sea is almost identical to the one of him in the river with Ali McGraw in The Getaway. They are both brief moments of respite. There’s also the small detail of both characters not being too far apart: one is a safe cracker, the other a bank robber.

There is so much in Papillon to admire that it is impossible to single out one individual moment; but mention must surely be made of when McQueen’s character finally cracks during his years of solitary confinement and, having cracked, decides to inform on Degas. Having decided, he can’t remember his friend’s name. As he struggles and cries, it is just plain heartbreaking.

Steve McQueen will always be thought of by a large section as the King of Cool; but as an actor it is as Papillon that film fans will remember him.

Recent Comments